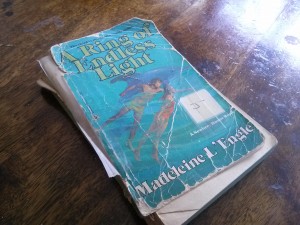

Before I started writing, I knew authors drew on their personal experiences to create realistic fictions. I learned this lesson in the 5th grade when I first met Jo March in Little Women: in a famous example of the write-what-you-know doctrine, Jo is encouraged to give up writing fantastical tales and instead write stories about the real world. Of course, authors who specialize in fantasy also draw on what they know, which I think I learned around the same time, probably from Madeleine L’Engle.

Before I gave this issue much thought, I imagined that drawing on personal experience meant giving your main character a twin brother because you have a twin brother or setting your novel in a small college town just like the one in which you live yourself. And it does mean that. But it also means building worlds out of tiny, seemingly insignificant remarks, images, and events. Authors collect these bits of reality and store them away until they discover that one of those bits is just what a character or a scene or a story needs.

In The Rosemary Spell, when the main characters go to their school library, I had in mind the library at Kilmer Middle School in Vienna, VA. I have only visited this school once, and I spent only a short time in the library, but the layout of the space, the light on the tables, it was what I needed, so I pulled it out of my memory bank and put it in the fictional school my characters attend.

I am currently in the process of revising a different book, and revising means lots and lots of deleting. Today I deleted a favorite scene involving a pigeon on a subway platform. The characters are traveling through Barcelona, and really, I just need to get them from point A to point B, but in the draft, I allowed the journey to take awhile, and I lingered over several stops along the way, trying to create a sense of the city. In revision, I realized that the journey was taking too long, and I had to face the painful fact that the pigeon was superfluous. So I cut him.

But cutting the pigeon feels wrong, because he’s real. When I was in Barcelona with my family, we saw a pigeon on the platform. Like my deleted fictional pigeon, he was fiercely protecting his territory, chasing people away and successfully keeping for himself a surprisingly large circle of platform–one pigeon all alone against the constant flow of people. It impressed me. I remembered it. And when I needed an image to show how fierce a small somebody could be, I summoned the pigeon. I plopped him on the platform on my page, and I let him hold his perimeter there.

At first, in the moment when I pressed “Delete,” I imagined that by cutting the pigeon, I was defeating him, a sad thought when what most impressed me was his strength and resilience. After holding all those people at bay, he was just callously deleted by the simple push of a button.

Drawing from personal experience comes with a sense of obligation that can make revision challenging. I feel a strange debt to the reality I ransack as I make my fictional worlds. Yet even though I cut the scene, the pigeon’s not gone. He’s safely stowed in my memory waiting his turn. Perhaps he will have a part to play later in the novel, or maybe this isn’t the right book for him, but he’ll show up in another book one day. At the very least, he’s here in my blog, still holding his own.